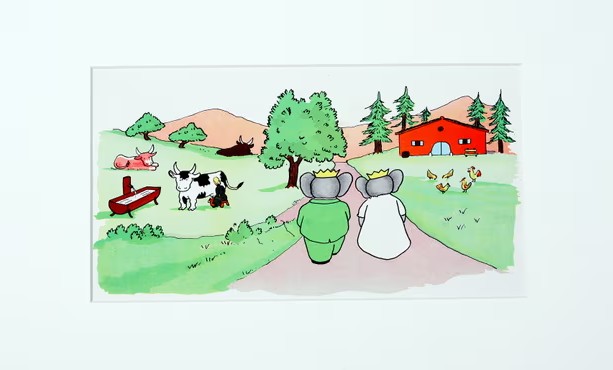

The storyteller and painter who brought back his father’s picture book series about the elephant king claimed not to have written specifically for children.

Laurent de Brunhoff, the author of Babar, passed away at the age of 98. He brought back his father’s well-known picture book series about an elephant king and oversaw its development into a worldwide multimedia property.

After receiving hospice care for two weeks, De Brunhoff, a native of Paris who immigrated to the US in the 1980s, passed away in his Key West, Florida, home on Friday, according to his wife, Phyllis Rose.

Laurent was just twelve years old when his father, Jean de Brunhoff, passed away from disease. However, he was an adult when he used his artistic and storytelling abilities to create hundreds of novels about the elephant who rules Celesteville, including Babar at the Circus and Babar’s Yoga for Elephants. Though he favored using less words than his father, he perfectly captured Jean’s subtle, elegant style in his pictures.

Author Ann S. Haskell said in the New York Times in 1981 that “father and son have woven a fictive world so seamless that it is nearly impossible to detect where one stopped and the other started.”

Millions of copies of the series have been sold worldwide, and it has been adapted for the big screen for films like Babar: King of the Elephants and Babar: The Movie. Maurice Sendak, who once said, “If he had come my way, how I would have welcomed that little elephant and smothered him with affection,” was among the admirers, along with Charles de Gaulle.

“Babar, c’est moi” (that’s me) is what De Brunhoff would say of his creation. In an interview with National Geographic in 2014, he said, “He’s been my whole life, for years and years, drawing the elephant.”

The novels’ popularity wasn’t shared by everyone. The scene in the first film, The Story of Babar, the Little Elephant, when Babar’s mother is shot and murdered by hunters scared away some parents. A number of critics labeled the series as racist and imperialist, pointing to Babar’s Parisian schooling as having influenced his (presumed) reign in Africa. The volumes are described as a “implicit history that justifies and rationalizes the motives behind an international situation in which some countries have everything and other countries almost nothing” by Chilean author Ariel Dorfman in 1983.

According to Dorfman, “Babar’s history is nothing more than the realization of the colonial dream of the dominant countries.”

Babar was defended by New Yorker contributor Adam Gopnik, who said in 2008 that the film “is not an unconscious expression of the French colonial imagination; it is a self-conscious comedy about the French colonial imagination and its close relation to the French domestic imagination.”

It was “a little embarrassing to see Babar fighting with Black people in Africa,” as De Brunhoff himself admitted. He specifically bemoaned the 1949 book Babar’s Picnic, which had obscene depictions of African Americans and Native Americans, and requested that his publisher remove it.

Jean de Brunhoff and painter Cecile de Brunhoff had three sons, the oldest of whom was De Brunhoff. When Babar’s wife, Cecile de Brunhoff—the namesake of the elephant kingdom—improvised a tale for her children, Babar was born.

In an effort to divert our attention, my mother began telling us stories, de Brunhoff said to National Geographic in 2014. We were enthralled with it and hurried to our father’s study, situated in a garden nook, the next day to share our excitement with him. Quite amused, he began to sketch. That was the beginning of the Babar narrative. In French, “baby,” Bebe elephant is what my mother named him. My father was the one who gave me the new name Babar. However, her journey began in the first few pages of the novel, with the hunter killing the elephant and the escape into the city.

Le Jardin Des Modes, a family-run publisher, produced the first edition in 1931. After Babar’s first success, Jean de Brunhoff wrote four additional Babar novels before passing away at the age of 37 six years later. Michael, Laurent’s uncle, assisted in the publication of two more pieces, but no one else contributed to the series until Laurent, who was a painter by then, decided to revive it during World War II.

He said in the New York Times in 1952 that “gradually I began to feel strongly that a Babar tradition existed and that it ought to be perpetuated.”

De Brunhoff was twice married; the most recent marriage was to Phyllis Rose, a critic and biographer who penned the text for some of the most recent Babar books, such as the 2017 book Babar’s Guide to Paris, which was touted as the series conclusion.

Antoine and Anne were De Brunhoff’s two children, although the writer did not intentionally write for young readers.

“Writing my books, I never really think about kids,” he said to the Wall Street Journal in 2017. “I used to make up tales in my head with my buddy Barbar, but not with children. I compose it with myself in mind.

“Writing my books, I never really think about kids,” he said to the Wall Street Journal in 2017. “I used to make up tales in my head with my buddy Barbar, but not with children. I compose it with myself in mind.