Since there were no indications of viruses or parasites, the enormous fatalities were confounding experts worldwide. Then we examined their skin in great detail.

The world’s amphibian scientists realized there was a problem while we were chatting in a hotel bar at the first global congress of herpetology: frogs, toads, salamanders, and newts were going extinct in large numbers worldwide, and no one knew why.

At the University of Kent’s 1989 conference, not a single session touched on the peculiar loss of amphibians worldwide. However, the accounts of several scientists were consistent: they were disappearing from Central America to Australia.

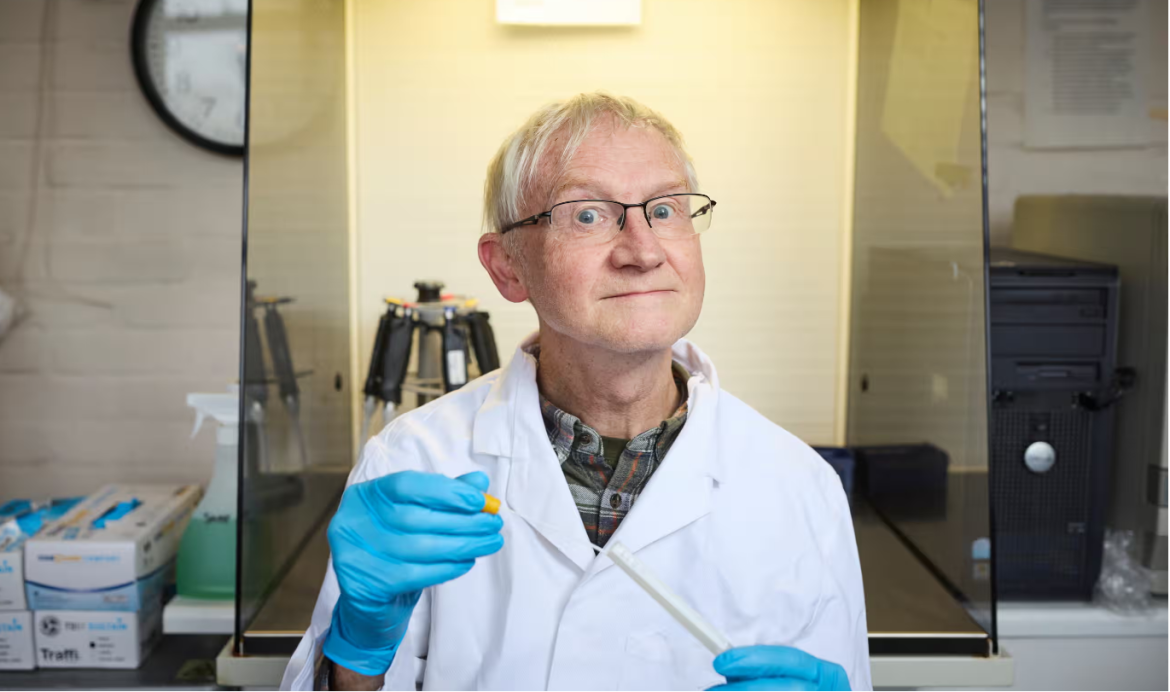

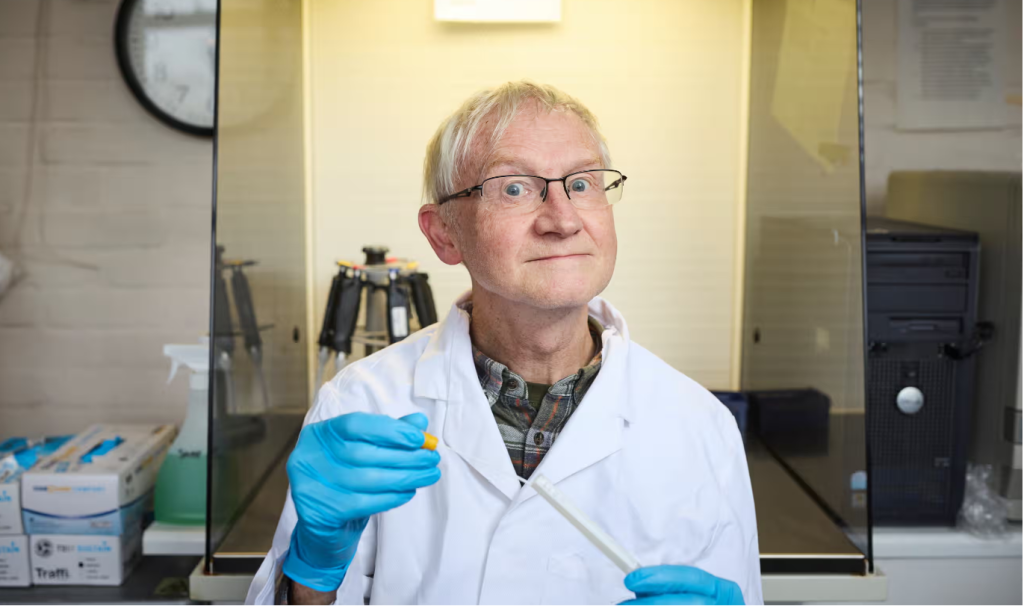

I became a veterinary pathologist member of the Zoological Society of London the previous year. It was my responsibility to investigate animal deaths. Not long after I started working here, people started phoning London Zoo to report that a large number of frogs had mysteriously perished in their yard. Reports of these incidents began to flow in more and more. As part of a PhD project, I began examining the deceased frogs to see what was going on, and I discovered that a ranavirus had been infecting frogs in England.

This was the first time a ranavirus has been discovered to be killing wild frogs in Europe, even though it was already well recognized in the US. I shared my research and received a request to assist with a fresh mystery in Australia. In a Queensland jungle, a master’s student was investigating a series of strange frog fatalities.

The animals who were dying there didn’t seem sick; their tissues were intact, they didn’t have parasites, and they had undergone testing for germs and viruses. Nothing. They had just passed away.

However, when I went over the proof, I realized I had already seen this. A few years before, when visiting Melbourne Zoo, I had seen some tadpoles belonging to a Queensland-based frog species that was in danger of becoming extinct. They survived well as tadpoles but perished as frogs. The frogs were confirmed to be healthy in all pathology examinations, with the exception of their death, save for the presence of an unidentified organism in their skin.

I examined the skin of the frogs from the Queensland rainforests that we had been studying with the master’s student. They had the same weird critters under a microscope that I had read about in the Melbourne Zoo’s pathology reports. Thus, we organized a test. A few healthy frogs were exposed to the contaminated skin. They all had the creature growing in their skin when they all died.

Concurrently, I was aware that colleagues in Panama were investigating the same issue. I instructed them to examine the deceased frogs’ skin to see if they had the same ailment. Indeed, they did. We combined our findings and published them in 1998, informing the public that frogs were being infected and dying worldwide by a fungus that would eventually be identified as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. The frogs had a rapid cardiac attack and perished as a result of it attacking their skin.

Since then, other researchers have confirmed our findings and discovered further strains of the fungus. The worst strain, which is still eradicating amphibians, seems to be just a century old and was most likely brought to every continent by people.

Hundreds of amphibian species have seen a fall in population, and around 100 species are known to have vanished in the last 50 years. One impacted species that I am researching is the mountain chicken frog, which was once widespread in the Caribbean but is now just 30 individuals strong. I may live longer than it. This illness serves as a constant reminder to me of the damaging effects that people may have on the environment and its biodiversity. Without us, this illness most likely would not exist. We need to figure out how to live peacefully with the amazing animals that inhabit our planet.

as conveyed to Patrick Greenfield